Mock Proposal: Training College Writing Tutors

In Summer 2025, I took the class EPOL 472: Instructional and Training Systems Design as part of the Instructional Design MasterTrack Certificate through the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Along with my group partners Karen McCurley-Hardesty and Ramona Magotsi, I created an instructional design project meant to provide training for professional writing tutors at Wilbur Wright College.

Of course, this was a mock proposal, meant only for class. Still, I was pleased to be able to apply my design skills to my former profession—I was a professional writing tutor for many years.

I wrote the Executive Summary and Background and Context sections for the project’s Needs Assessment. I was also responsible for Module 1: Tutor Employee Requirements, in which we proposed training for new hires. This includes Module 1’s Learning Outcomes and Instructional Strategy. Beyond that, my group collaborated on learner analyses, task analyses, assessments, proposed budgets, and a formative evaluation plan.

This project gave me invaluable experience with creating an ID project in a group setting. I am sharing some deliverables below.

Here are some links to the different parts of my sample:

1: Executive Summary

Wilbur Wright College, one of the seven City Colleges of Chicago, offers writing-specific tutoring for students in its Writing Center. This center employs 12 professional tutors and conducts thousands of appointments per year. As successful as it is in serving Wright College’s students, professional issues are hampering the Writing Center’s tutors and the tutoring program in general.

Due to many changes in leadership and personnel in recent years, the Writing Center lacks formal onboarding, pedagogical unity, and consistent interactions with students and their work.

The lack of onboarding is especially problematic as professional writing tutors at Wright College are expected to use the application Navigate 360 to record tutoring details, access student information, and maintain schedules. Tutors are also expected to demonstrate best practices regarding privacy with student educational information, again, often without any training. And, as do all employees of the college, tutors have the responsibility to attempt to diffuse aggressive behaviors and play specific roles in emergency situations.

Beyond the expectations of being an employee, the professional writing tutors of the Writing Center must also execute their jobs as tutors. This is often made more difficult by the absence of established routines and best practices. As opposed to other tutoring centers, tutors at the Writing Center are not trained in how to interact with students. Lacking a formal structure for engaging with students and the work they bring in, tutors are left to guess at how to work with the diverse student population that Wilbur Wright College contains.

While the Writing Center may offer independence that some tutors may welcome, others complain of the lack of pedagogical vision. In recent years, tutors at Wilbur Wright College’s Writing Center have not received any professional development, nor are they prescribed unifying evaluation techniques or negotiation strategies. Instead, tutors are left to toil as they see fit, not receiving support or guidance from their department. Inevitably, this trickles down, and Wilbur Wright College’s students do not receive the levels of consistent support that they deserve.

Our plan addresses the major gaps that the professional writing tutors at Wilbur Wright College’s Writing Center are currently facing. We propose a training consisting of three modules. In Module 1, tutors would receive the instruction they need to fulfill the requirements of their employment regarding record-keeping, interacting with student educational information, and safety and respect concerns. In Module 2, tutors would receive training on how to effectively and consistently run their tutoring appointments. In Module 3, tutors would acquire and absorb the pedagogy behind the evaluation and negotiation necessary for writing tutors at the college level.

As a result, we anticipate less frustration and higher motivation for the professional writing tutors of Wilbur Wright College’s Writing Center. We also expect the Academic Support Services Department to be more satisfied with the Writing Center’s performance. Lastly, we predict far better support will be given during the thousands of appointments the students of Wilbur Wright College receive in the Writing Center every year.

2: Background and Context

Wilbur Wright College is one of the seven community colleges run by the city of Chicago, Illinois, USA. It had a total enrollment of 7,789 in the 2023-24 academic year, 2,304 full-time and 5,485 part-time students (UnivStats, n.d.) Since 2012, it has been City Colleges’ College to Careers hub for Information Technology programs. Despite this designation, Humanities classes make up the bulk of the courses offered at Wilbur Wright College, and there are dozens of sections of First Year Composition (English 096, English 101, and English 102) running each semester.

Because of the need to help Wilbur Wright College’s student population with writing services, the English, Language, and Reading Department partnered with the Academic Support Services Department to create the Writing Center, a tutoring center that concentrates on assisting writing across the entire college. The Writing Center now falls entirely under the Academic Support Services department, and its immediate supervisor is the Director of Academic Support Services.

It is notable that the Writing Center at Wilbur Wright College only employs professional tutors. As opposed to peer tutors, professional tutors are not current students and either teach the subject they tutor or have relevant expertise in their tutoring subject. While this may seem advantageous to both students and the Writing Center—and is often advertised as such—the professional writing tutors often face gaps, especially when they are first hired.

Several problems exist, one being that while professional writing tutors at Wilbur Wright College may have expertise in writing, they are not necessarily trained in how to tutor writing. For example, some tutors who are Composition teachers are hired based on their teaching experience, and while teaching and tutoring are related, they have differences that can be difficult to navigate. Whereas peer writing tutors might be required to receive training on the fundamentals and principles of tutoring, professional writing tutors at Wilbur Wright College are not.

Another issue is how colleges require records to be kept after tutoring appointments. Even if professional writing tutors have experience using recording software at another institution, different colleges invariably use different software and require different information to be recorded. Besides notes needing to be accurate and complete to the college’s specifications, the utmost care needs to be taken regarding student privacy laws such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA. Training on such software and on such requirements can often be scanty.

The above problems may be directly addressed by mission statements or best practices of the college and/or the academic support department that a professional writing tutor works for—but at Wilbur Wright College’s Writing Center, they are not.

In any case, something that is much harder to define by any school is the connection between writing tutors and the teachers employed by the school. Instructors giving assignments, students bringing in those assignments to tutors for help, and tutors providing that help, make up an important ecosystem that needs to be maintained. But like other ecosystems, this balance at Wilbur Wright College can be incredibly complex, delicate, and often completely unspoken.

Professional writing tutors at Wilbur Wright College’s Writing Center face a variety of challenges that they may be unprepared for. Training would help alleviate these problems, or at the very least, identify them.

We identify the gaps facing professional writing tutors at community colleges through personal experience. Steve Bogdaniec worked as a professional writing tutor at Wilbur Wright College, one of the City Colleges of Chicago, for 11 years. Steve was hired because he taught Composition at the school at a time when the tutoring center needed tutors. He had no tutoring experience, and apart from some random professional development workshops given years after being hired, he never received any training. A training program addressing the gaps mentioned above would have helped Steve immensely.

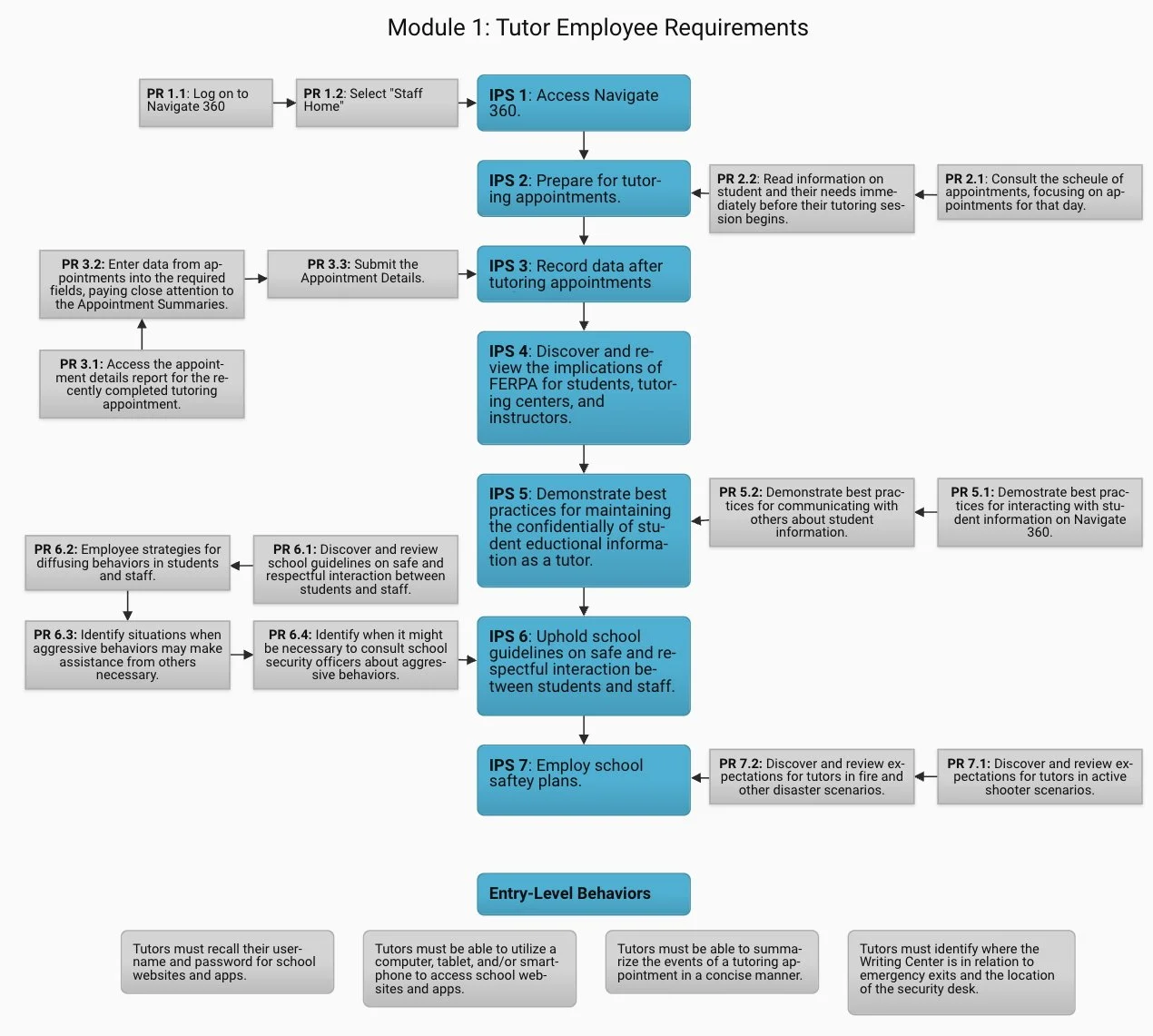

3: Learning Outcomes (Module 1)

Module 1 Learning Outcome: After completing Module 1, writing tutors will be able to effectively use the management system for accurate and consistent record keeping and will identify potential issues regarding student privacy and safety.

Informational Processing Steps

Access Navigate 360.

Prerequisite 1: Log on to Navigate 360.

Prerequisite 2: Select “Staff Home.”

Prepare for tutoring appointments.

Prerequisite 1: Consult the schedule of appointments, focusing on appointments for that day.

Prerequisite 2: Read information on the student and their needs immediately before their tutoring session begins.

Record data after tutoring appointments end.

Prerequisite 1: Access the appointment details report for the recently completed tutoring appointment.

Prerequisite 2: Enter data from appointments into the required fields, paying close attention to the Appointment Summaries.

Prerequisite 3: Submit the Appointment Details.

Discover and review the implications of FERPA for students, tutoring centers, and instructors.

Demonstrate best practices for maintaining the confidentiality of student educational information as a tutor.

Prerequisite 1: Demonstrate best practices for interacting with student information on Navigate 360.

Prerequisite 2: Demonstrate best practices for communicating with others about student information.

Uphold school guidelines on safe and respectful interaction between students and staff.

Prerequisite 1: Discover and review school guidelines on safe and respectful interaction between students and staff.

Prerequisite 2: Employ strategies for diffusing aggressive behaviors in students and staff.

Prerequisite 3: Identify situations when aggressive behaviors may make assistance from others necessary.

Prerequisite 4: Identify when it might be necessary to consult school security officers about aggressive behaviors.

Employ school safety plans.

Prerequisite 1: Discover and review expectations for tutors in active shooter scenarios.

Prerequisite 2: Discover and review expectations for tutors in fire and other disaster scenarios.

Entry-Level Behaviors:

Tutors must recall their username and password for school websites and apps.

Tutors must be able to utilize a computer, tablet, and/or smartphone to access school websites and apps.

Tutors must be able to summarize the events of a tutoring appointment in a concise manner.

Tutors must identify where the Writing Center is in relation to emergency exits and the location of the security desk.

Informational Processing Steps (IPS) and Prerequisites (PRE) Map

4: Instructional Strategy (Module 1)

Instructional Strategy

Module 1: Tutor Employee Requirements would feature an instructor leading tutors in a computer lab or remotely. The instructor would lecture using PowerPoint slides, and it would be up to the instructor’s discretion when—or if—to pause to invite discussion. This seems advisable given the subject matter, which is mostly declarative knowledge and application based. At two points, the instructor would stop to give discussion activities, as will be covered below.

Here is an overview and rationale of the instructional strategy for Module 1, broken into Introduction, Body, and Conclusion, and Assessment for Lessons:

INTRODUCTION

Deploy attention to the lesson

To begin, the instructor should appear on screen and welcome tutors to the instruction, briefly introducing themselves. While welcoming tutors in, the instructors should reinforce the title of the module: this is about a tutor’s expectations and requirements as an employee. As such, it may be less exciting or stimulating than other modules in the training, and the instructor should make light of this with light humor. The instructor should then reinforce that the information was important to a Writing Center’s tutor’s day-to-day and would definitely make that aspect of the job easier.

It would be left up to the instructor’s discretion as to an icebreaker for the tutors. In the interests of time, it would not be recommended for groups over 10. There would not be much time for an icebreaker in any case.

Tutors would be settling into the instruction and possibly engaging in a short icebreaker. The hope is that tutors would welcome the recognition on the instructor’s part that the training would not be viewed as exciting and would appreciate the humor that was attempted. Another expectation is that their attention would be heightened by the promise of the training being important to their day-to-day operations as a tutor

Establish instructional purpose

The instructor would start the PowerPoint and reinforce the second slide: the training is designed to address three vital areas for tutors as employees of the Writing Center and Wilbur Wright College. They would state that the module looks at real world examples, screenshots, and hypotheticals to communicate this. Tutors would break off into groups twice to practice aspects of the training, and each would take a post-assessment quiz on their own to evaluate their comprehension.

Again, the instructor should verbally reinforce that the content in Module 1 will be applied in a tutor’s day-to-day operations, and this time. This should communicate to tutors that the overarching goal of the training is application of what they will be covering—with a small amount of problem-solving thrown in.

Tutors would learn the instructional purposes behind the training: application and problem-solving.

Arouse interest and motivation

By the time the Introduction is over, the instructor should have aroused tutors’ interest and motivation by the promise of immediate application of the knowledge and skills about to be covered.

The expectation is that tutors would be interested and motivated by the mentions of immediate application and importance to their jobs. According to Smith and Ragan (2005, p.223), “problem solving, if completed successfully, can be motivating in itself.” Tutors would not solve problems during the Introduction, but by the end of the instruction, tutors would have solved two problems in group activities. Hopefully, these activities will be successful.

Preview lesson

At the end of the Introduction, the instructor would briefly preview the three areas of the training:

1: Using the Navigate 360 application for scheduling, keeping records of appointment details, and accessing student educational information.

2: The implications and requirements surrounding student educational information as a tutor

3: Safety and respect concerns as a tutor, especially what is expected of them in this regard.

Here, instructors should note that this module will not touch on pedagogy or any best practices for actual tutoring. This is more about the “nuts and bolts” of being an employee who is a tutor, not instruction on actual tutoring. That, the instructor should announce, would begin in Module 2.

Tutors would discover the outline of Module 1 and would know, on a macro level at least, what to expect and when.

BODY

Recall relevant prior knowledge

Instructors would assume entry level behaviors are met and that tutors are conversant with computers, using log ins, and working in a professional environment. As such, instructors would be calling on prior knowledge regarding needing to log in, schedules being available online, records being kept online, and overall, having professional expectations. It could be implied, but perhaps not stated, that when working in the Writing Center, tutors would have a direct supervisor who will have access to their work, and that they need to meet professional requirements.

Beyond that, each training area would build on prior knowledge and competency as instruction goes on. In the Navigate 360 section, for example, the instructor would use screenshots of the apps that would build on familiarity already established. In the Safety and Respect section, the ways tutors are expected to act in active shooter emergencies and disaster emergencies will be compared and contrasted, and the instructor would bank on recall of one to be able to contrast the other.

It would be up to the instructor’s discretion to review the declarative knowledge that has already been applied, especially right before the two group activities. These would require tutors to recall prior knowledge in order to imagine and write about hypotheticals based on those two areas of the job, and it may be fruitful to jog the tutors’ “working memory” (Smith & Ragan, 2005, 224).

Tutors would be expected to recall prior knowledge as the training goes on. It would be up to the instructor’s discretion whether to remind them of key points or even to question them on material already covered.

In any case, tutors would be required to engage in two group activities and a post-assessment quiz. Both require accessing prior knowledge.

Process information and examples

In the first lesson (Navigate 360), the instructor would mostly rely on the PowerPoint to provide information and examples. Images of the Navigate 360 application should be especially helpful to connect what tutors are learning about with the exact locations of such menus and buttons. Also, a helpful mnemonic would be shared for writing Appointment Summaries after tutoring sessions: Past, Present, Future. Tutors should write why students came to the Writing Center (past), what the tutor and student worked on during the session (present), and what the student indicated they will do as a result of the session (future). This is a concise outline that also fits the best practices of what is expected of an Appointment Summary, and it is expected that tutors will be able to process the mnemonic easily.

It is hoped that the supplantive approach taken will not bore tutors who would have higher aptitudes than anticipated. Also, it would be ideal if tutors who require clarification or further explanation take the opportunity to stop the instructor and ask for help. Too often in lecture situations, which large parts of Module 1 will be, learners do not speak up. The PowerPoint being made available and the instructor pausing to field questions will, at least, give the learners the chance to slow down the instruction to process it. There will also be group situations during which tutors will interact and potentially process information and examples together.

Focus attention

The instructor would be given PowerPoint slides and group activities to work with. Still, it would be up to the instructor to decide how to lecture, whether to ask leading questions, how to facilitate discussion, and to oversee the presentations after group activities. In other words, the instructor should use their discretion based on their experience, feel for the material, and their appraisal of the tutors.

How well the tutors are able to focus depends somewhat on the content and plans made here, but the tutor will play an active part as well. Will they be receptive to a module that directly applies to their jobs, or will they dismiss it as yet another professional training that could be largely ignored? Or will it be a combination of both? Just as with an instructor’s ability to focus attention, some of this is beyond the scope of planning.

Employ learning strategies

Much of the material covered in Module 1, especially the structure of the Navigate 360 application and the laws governing student educational information, falls under what Smith and Ragan (2005, p.152) call “declarative knowledge.” This involves the “labels and names” and “facts and lists,” (Smith & Ragan, 2005, p.152) that Wilbur Wright College and the Writing Center want their employees to understand and apply. As such, some strategies that will work with declarative knowledge are the use of screenshots as imagery, especially with Navigate 360, and the mnemonic of “past, present, future” when writing Appointment Summaries (Smith & Ragan, 2005, p. 163).

However, there are areas of Module 1 where the instructor would try to promote problem-solving, such as when identifying and attempting to reduce aggressive behaviors in the Writing Center. Here, the instructor would follow Smith and Ragan’s (2005, p.225) suggestions for using “alternate ways of representing the problem” and “monitoring techniques for appraising the appropriateness of the solution” instead of relying on the “labels” and “facts” of the declarative knowledge taught elsewhere.

It is anticipated that tutors will recognize that the strategies of what is being taught to them will change based on its content and will approve of the changes

Practice

Because of the amount of information covered here—each of the three sections could conceivably be its own module—there is not much time to allow tutors to practice the material. Also, there would be far more opportunities to practice using the Navigate 360 application than to simulate an active shooter emergency.

However, tutors would be engaging in two group activities that will allow them to practice two important aspects of their job. Instructors would be explaining that practice before the activity, answering any questions the groups have about practicing during the activity and directing the discussion about the practice after the activity. The instructor would play the biggest role by leading the discussion after the activities. They will call on groups, judge where, how, and how long to lead discussions, and potentially apply their own experiences to the group’s findings.

In creating these practices, it should be assumed that while tutors will not be complete novices, they will not be experts either. Care was taken when writing the group activities to give tutors “problems that have easily recognizable, distinctive features in given and goal states, with little extraneous detail” (Smith & Ragan, 2005, p. 226). Also, as Smith and Ragan (2005, p. 164) point out, it is preferable when working with novices to create practice that demands “recognition” rather than “recall,” as recognition is less taxing, cognitively speaking.

Hopefully, these efforts will have the desired result of offering practice that will fit all experience levels.

Tutors would be practicing at two different points of the module, and it is expected that these practices should benefit their problem-solving skills as they relate to their jobs. But again, more practice would be ideal and would be offered if there were more time.

Evaluate feedback

For most of Module 1, it is left up to the instructor how much to engage tutors in activities that will lead to feedback. The instructor could ask questions, and as a result of the answers, offer tutors feedback.

That said, the two areas that will definitely offer feedback to evaluate will be during the group activities. Each group would present their findings to the instructor and the rest of the class, and the instructor would respond to these presentations.

It would not be accurate to say that there are no “right or wrong answers,” especially when regarding student educational information or safety concerns. There could be some very “wrong” answers, along with some potentially damaging real world consequences. Still, the instructor should be supportive and should “include information regarding not only the appropriateness of the learners’ solutions but also the efficiency of the solution process” (Smith & Ragan, 2005, p. 226). Although the cliché of no “right or wrong answers” may not apply, another one should work here: the instruction is a “safe space” in which tutors should feel free to make mistakes in pursuit of future competency.

Again, how much tutors interact with the instructor outside of the group activities would largely be up to the instructor. Ideally, if tutors had feedback during these times, such as requiring clarification on a point, tutors would speak up or type in chat, and they should be encouraged to do so.

The two group activities require tutors to offer feedback, but because of the nature of groups and there only being one person per group presenting to a class, many tutors might not make themselves heard at all. This is unfortunate, and future iterations of this module should seek to find ways to hear from everyone, even if only a small amount, during the instruction.

CONCLUSION

Summarize and review

Instructors would end the instruction by referring to the high points of each section. There would be three devoted slides to this, one for each of the three sections.

Tutors would read (and hear the instructor describe) the three summary slides.

Transfer learning

It is anticipated that the material in the Navigate 360 section would immediately transfer to tutors. Tutors would be using this application multiple times a day once they began working in the Writing Center, and the repetition should make it easier to retrieve the pertinent information (Smith & Ragan, 2005, p. 166).

The information from the other two sections may need to be reinforced with repeated trainings, perhaps once a year, in order to fully see transfer. The same might be true for the problem-solving skills taught in the module. Still, Smith and Ragan (2005, p. 226) suggest that transfer could be made easier if the “utility” of learning problem-solving is made clear to learners. Also, as with using the Navigate 360 application, tutors should get continuous practice with problem-solving in their day-to-day activities, so transfer should be aided.

The outlook for the transfer of the Navigate 360 section seems brighter than those of Student Educational Information and Safety and Respect Concerns. It might be advisable to reinforce those areas yearly. Still, as Smith and Ragan indicated, the importance of those areas to their employment may cause them to transfer more easily.

Re-motivate and close

After reinforcing why the instruction was given and how the skills and knowledge covered will apply to the tutors moving forward, the instructor must bring up the post-assessment quiz, the details of which will be given in its own slide. On that slide, tutors would be recommended to have the PowerPoint open when they take the quiz. The link for the slides would be given on the slide, and the link would also be emailed immediately after the instruction.

After that, the instructor should use their personality to motivate and say goodbye as they see fit.

Tutors would be made aware of the details of the post-assessment quiz, which they will take on their own. Hopefully, they would see the instruction in Module 1 as worthwhile.

ASSESSMENT FOR LESSONS

Assess performance

Tutors would be given a post-assessment quiz. The quiz would be multiple-choice and would assess the declarative knowledge given in the module. As such, it would test the ability of the tutors to recall the information taught in Module 1, not the ability to apply the knowledge (Smith & Ragan, 2005, p. 167). There would be 15 questions, and 12/15, or 80%, would be considered mastery.

Still, as the quiz would be “open book,” and indeed, since tutors would be given access to the PowerPoint slides (and thus the answers), the intention of “recall” vs. “recognition” from above is echoed. It would be more important for tutors to recognize the declarative knowledge from Module 1 than it would be to memorize it.

In contrast, the instructor will be assessing performance themselves in the two group activities. This would be done via rubric, and the rubrics would assess how the groups solved the problems using the information from the instruction. This would also contrast with the declarative knowledge assessed in the post-assessment quiz as the rubrics would judge how tutors applied the knowledge from the instruction, not how they remembered it.

Immediately after submitting the quiz, tutors would receive their scores and automated comments on the quiz platform. They would also receive these via email. They would not receive scores from the rubrics for the two group activities as those are meant for internal assessment.

Tutors would be taking a post-assessment quiz that must be considered easy by any standard, especially since the answers will be in the slides they will be encouraged to have open while they take the quiz. Still, random guessing due to not paying attention could easily lead to a score below the mastery level.

The rubrics assessing the two group activities would have to be considered “easy” as well. They are meant to assess more about how the groups solved problems and applied what they learned in the module, and the single criterion on the rubrics is not rigorous.

It is hoped that tutors will not use the ease of these assessments as an excuse not to take them seriously.

Evaluate feedback and seek remediation

The scores on the rubrics and quizzes would be analyzed to see if individuals’ scores differed from their group’s scores. After these scores were analyzed, decisions would be made regarding changes to the instruction and activities.

It is unclear what role tutors would have in evaluating feedback or seeking remediation.

Thanks for reading my work on this mock proposal! If you have questions or comments, contact me at steve.bogdaniec@gmail.com.